Morris Goldstein, a near forgotten member of the remarkable group of artists and writers that flourished in the East End in the early part of the last century, deserves wider recognition. RAYMOND FRANCIS, his son, gives us a taste of his story in this extract from his book about his father's life. This article was published in JEECS's magazine The Cable in 2016 and is repubished here to mark the book launch on Tuesday December 5 2023. For details, see our events page.

On January 15 1892, Morris Goldstein is born in Pinczow – a small town in Poland midway between Krakow and Warsaw.

It is the height of the pogroms. A campaign of extreme religious persecution prompts the mass emigration of Jews. In 1900, Morris’s parents, David and Sarah, decide that they too have to leave. Together with his sisters Annie and Jennie, they escape from Poland and join over 100,000 Jews who also flee to the East End of London.

The East End is a sprawling slum; a colony of East European Jews. It is not long before newspaper column inches start filling up with talk of being ‘overcrowded’ and ‘swamped’ my migrants. It would be a language that attached itself to the waves of migrants that would follow long after the Jews had left.

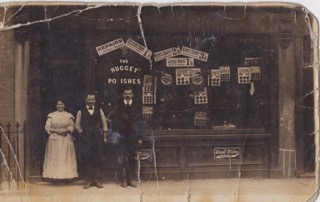

Whitechapel would become Morris’s home for the next 45 years, and an area from which would emerge some of the 20th century’s finest artists. The family rent a house on Redmans Road, and, like thousands of others, struggle to make ends meet. They trade as bootmakers and set up a shop called the Nugget Polishers for repairing boots and shoes. They take home about £2 per week. The signs on the shopfront read “Gents’ Boots – Soled and Healed”

Morris would attend schools in the East End, at Jamaica Street, Smith Street and The Arts and Crafts School in Stepney Green. It is

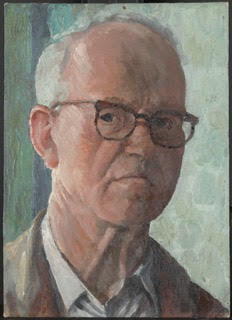

Morris Goldstein: self-portrait c. 1960

here that he becomes friends with Isaac Rosenberg, who would later become a celebrated poet.

In her biography of Isaac Rosenberg, The Making of a Great War Poet, Jean Moorcroft Wilson writes: “Goldstein understood the conflict between dreams and reality. Though studying pure art at the Stepney Green school he knew that the need to earn a living at 14 would prevent him from pursuing it full time.

“Like Rosenberg, he would be obliged to take up an apprenticeship in commercial art, in his case marquetry. More practical than his friend, he would persuade Rosenberg to continue his art studies alongside his wage earning…and would introduce him to other like-minded people in their district….Rosenberg was lucky to meet Goldstein when he did.”1

Sarah and David Goldstein in front of the Mile End boot shop that was their family business, c.1905.

A sign outside the shop read: “Gents’ boots soled and healed”.

Joseph Cohen notes in his book Journey to the Trenches that Rosenberg and Morris “became sufficiently good friends as Isaac would read his poems to him and ask for his reaction”. 2

Morris and Rosenberg, both driven by their passion to become respected artists, spend much of their time at Whitechapel Art Gallery – it was a haven from the reality of life outside. It is here, that they meet Mark Gertler, another aspiring artist. Over time this group of friends expands to include David Bomberg, Jacob Kramer and John Rodker – a remarkable group of artists and writers who would later become known as the Whitechapel Boys.

Morris also befriends the writer Joseph Leftwich, who was writing an extensive diary about East End life throughout 19113. Morris is mentioned on a number of occasions. Leftwich notes that Morris introduced him to the artist Mark Gertler; there are Young Socialist League meetings they attended together in Mile End; concerns about anti-Jewish riots in London and Manchester; and a revealing observation about Morris during a performance of Elijah at the People’s Palace theatre.

His entry on April 15 1911 reads: “Goldstein sat near us and seemed greatly interested in my face and my expression whilst I listened. At least Sig noticed his looking intently at me and drew my attention to this. As we went on Goldstein said he had taken a great liking to me and would I consent to sit for a portrait for him. For nearly three weeks now I’ve been working for Morris as his managing clerk at a salary of 16 shillings per week….”

According to Sarah MacDougall in London, Modernism and 1914, many of the Whitechapel boys flirted with

“Rudolph Rocker’s anarchist movement and several of them – Leftwich, Rodker,

Goldstein and briefly Bomberg – were later communists, while Leftwich and Goldstein were committed Zionists.”4

By night Morris and Rosenberg attend London County Council School of Photo-engraving and Lithography in Fleet Street, otherwise known as the Bolt Court Art School5. In 1912, aged 20, Morris is awarded the medal for best work.

Morris Goldstein’s mother had become a very close friend of Hacha (Anna), Isaac Rosenberg’s mother, and they often commiserated with each other that they both knew of young tailors in the neighbourhood with regular earnings of £15 – £20 per week, while their sons Isaac and Morris brought in nothing.6

Morris Goldstein in 1909, aged 17

Meanwhile Morris’s dreams of getting to the Slade School of Art are starting to fade. For many years he applies to the Jewish Educational Aid Society for a grant to cover his fees at the Slade. His application for funding is turned down on three separate occasions between 1908 and 1911, but he continues to persist.

On April 21 1913, when he was living in Hartford Street, Mile End, he writes again to the Jewish Educational Aid Society7: “You are undoubtedly aware that in October 1911 I approached the JEAS for assistance to enable me to continue my art studies and was advised to continue the work in which I was engaged. Working on the advice of your society I attended evening schools and utilised all my spare time to the best of my ability. I am pleased to inform that last year at Bolt Court School I gained several prizes…for work executed at the school.

“I regret to say that trade became very slack and consequently the firm with which I was engaged was unable to find sufficient for me to do and I had to therefore discontinue my work.

“However, realising my position and knowing full well that my parents could not possibly assist me I was economical and saved a little to help myself. I felt and believed that I possessed the ability and therefore did not wish to neglect art and consequently attended at the Slade School for a term and a half and received much encouragement from the professors. It is my heartfelt wish to realise my ambition to achieve success in the art world and if I can possibly secure your co-operation I feel I shall do so.

“If therefore you could see your way to again consider my application for assistance I should feel extremely grateful.”

The JEAS was “the only charity to play a significant role in the social history of art in the pre-war period…..all grants were in fact loans to be repayable out of subsequent income, and the applicant with a parent or guardian as surety signed a formal agreement to this effect. In fact the committee went to some lengths to pursue unpaid loans, on principal and in the interests of future applicants.”8

His letter pays off and the JEAS offer him financial support, enabling him to continue studying at the Slade. Among his fellow students are David Bomberg, Isaac Rosenberg, Joseph Kramer and Bernard Meninsky, who also receive grants from the JEAS.

This group of East End Jewish artists at the Slade “were set apart from the other students as they had little money and could not return hospitality or pay for cafés or music halls. Rosenberg, Bomberg and Morris walked daily from Whitechapel to Gower Street to save the tube fare.” 9

Between Morris, Bomberg, and Rosenberg “an abrasive competitiveness was asserting itself. Each bragged about his accomplishment and then gossiped to the others. Morris and Bomberg thought Rosenberg a good poet but no painter, while Rosenberg dismissed their own claims with unabashed sarcasm.”10

Morris introduced them all to Sonia Cohen, a pretty local Jewish girl who had been brought up in an orphanage and worked in a sweatshop but also wrote poetry. They all made advances to her. She went out with Morris for a while; Bomberg sought unsuccessfully to seduce her; Rosenberg wrote her poetry and painted her portrait; but John Rodker who ‘scoffed’ at her poetry, succeeded” 11

This group of friends would meet in the Domino Room at the Café Royal in Regent Street in the West End, “an exuberant vista of gilding and crimson velvet set amongst…opposing mirrors with fumes of tobacco ever rising to the painted and pagan ceilings”.12

Morris described it as “‘The Mecca’ and remembered going there quite a lot and making his sixpenny coffee and cake last all day. Rosenberg was often with him and Morris recalled that they hoped to meet literary personages to get their opinion on his work”.13

At the Slade under the tutelage of Frederick Brown, Morris is in his element.

Slade classes were “scheduled for Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays and Kramer and Morris were there on those days and they often drew side by side. Not infrequently Rosenberg would pass them fragments of paper on which he scrawled some verses”.14

Between 1912 and 1913, Morris wins a prize for head painting (£2 10s) and certificates for painting, perspective and drawing. His fellow student Dora Carrington is awarded first prize for figure painting and painting from the cast. She would later find herself in a love affair with Morris’s friend Mark Gertler.

The year after Morris leaves the Slade, the Whitechapel Art Gallery stages an exhibition called Twentieth Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements.

The gallery invites Morris’s friend David Bomberg and Jacob Epstein to create a Jewish section “which finally comprised 54 works by 15 different artists...and as the Jewish Chronicle noted ‘it was the first real attempt to organise a collection of works by Jewish artists…The majority of artists grouped together in the Jewish section represented an extra-ordinary group of avant-garde painters most of them students or graduates from the Slade School of Art who each claimed a link with the East End itself.”15

Morris exhibits five paintings in the show: Fear, Les Miserables, A Rabbi, Head of a Musician, and A Study. A Rabbi is the only explicitly Jewish-themed work in the exhibition. This show would be the first and only time Morris and the other Whitechapel Boys exhibit together.

Three months later, on July 28, the First World War breaks out. Morris is exempt from fighting because he is not naturalised as a British citizen. Nevertheless, like many of the Whitechapel Boys, he is against the war.

“Mark Gertler thought it was ‘wretched, sordid and butchery’ and became a conscientious objector”16 as did Leftwich who is imprisoned when conscription begins.

During the war years Morris shares Mark Gertler’s studio17 and continues to exhibit in the East End. In 1914, he shows A Study, The Talmudist, Sabbath Eve at the New English Art Club. In 1915, his paintings The Tempest and The Student are reproduced in Colour, a high-quality magazine covering contemporary art in Britain and overseas.

In May 1916, Morris’s friend Mark Gertler writes a letter that sums up the challenge for his contemporaries at the time: “I hate with all my being the idea that money should be able to influence my freedom. It is terrible to think that the more interesting my work becomes the more difficult it becomes to sell them and to live!

“If it was not for money really I should be happy, because I only really ask of life to be allowed to paint to be allowed to dig deeper and deeper in the wonderful mysteries of art. But if one has no money the purity of one’s art studio are spoilt because one can’t help sometimes thinking of what the Stupid buyers would like as one must live…to be good artist one must have an income.

“Let no person come and tell me that poverty is good for an artist. If an artist is poor he simply has to please if not always then sometimes. I shall paint what I like.”18

He concludes, “I am working on a large very unsaleable picture of Merry-Go-Round, I am so excited about it. It will be finished in a few weeks.”

This painting, exemplifying the futility of war, would become the most saleable and celebrated work of art he would ever create.

Morris also sought to represent the war, which had already cost the lives of millions of soldiers, in his work.

The New English Club exhibits his painting The Sacrifice: Incident of the Present War. Two years later Morris would learn that his good friend Isaac Rosenberg has been killed in the Battle of the Somme, fighting on the Western front in the closing stages of the war.

During this time Morris starts teaching art classes at Toynbee Hall in Aldgate East, where he becomes the Art Master. Toynbee Hall was Britain’s first university settlement to bring Oxbridge students directly among the poor, in an attempt to improve the quality of their lives through education.19

Meanwhile having left the Slade, Morris struggles to pay off the loan from the JEAS.

On December 26 1917 he writes to the JEAS:20 “I am alive and that is a great deal in these days. To be alive is a great benediction – to live through these turbulent times until peace reigns once more upon earth would be the greatest joy of all.

“My present hope and wish is to live through these times so that after the cessation of hostilities I could put my body and soul into my spiritual work. I am not yet in the army but of course I'm liable to be called up any day now.

“Let us hope the war will end soon,

“Believe me to remain,

“Morris Goldstein.”

The JEAS would continue to chase him for the next 20 years to repay the loan. JEAS recipients almost never managed to pay off the debts in later life and must have felt under pressure by the constant reminders.

Meninsky offered to settled his debts with pictures in 1930, and Gertler pleaded poverty several times in the coming years; his debt was only finally written off after his suicide in 1939; Bomberg’s outstanding loan was eventually written off in 1953 just four years before his death; and Morris was pursued by solicitors in 1931 for outstanding debt of £142 13s, despite being in a state of undischarged bankruptcy.21

On January 2 1920 in Mile End, he marries Sivia Gracerman. They would have three children: Rita, David and Priscilla.

That same year Morris has three more works shown at Whitechapel Art Gallery, with the Toynbee Art Club: My Mother, The Wanderers and A Study. In 1923 he exhibits again at Whitechapel Art Gallery as part of a show entitled Works by Jewish Artists. His works have the titles A Spanish Girl, Portrait and Clara. Through his portraits of ordinary people, Morris becomes a chronicler of East End life.

To make ends meet, he continues as a marquetry cutter and later finds work travelling as a sales representative for a women’s fashion house. The financial demands placed on him as a young father with a growing family restrict him from furthering his artistic career. It will be another 30 years before he is able to exhibit his art again.

The artist in 1965 with his painting Les Miserables, which had been exhibited at the Whitechapel Art Gallery

On June 29 1940, from his home in Valance Road in Whitechapel, as air raid sirens envelop London, he writes to his estranged aunt and uncle in the US: “We now look to you Americans to save some of our children from this horrible war. Will you help us?”22 He hopes that his estranged family in New York will provide a safe haven for his three children while Britain remains at war.

During this period, he continues to pursue his passion for art, but he cannot make a living from it. This contributes to the breakdown of his marriage. He also discovers that his wife, Sivia, was never divorced from her first husband. In November 1942, in London’s High Court, his marriage is annulled.

Three years later, in 1945, having moved to Stamford Hill in north London, he marries his second wife, Bella. Two years later, aged 56, he has another child, Raymond.

In 1953, nearly 40 years after his first show, he returns to the Whitechapel Art Gallery where he exhibits a mixture of pastels, oil paintings and watercolours as part of the East End Academy annual show. He continues there nearly every year thereafter until 1960. His works included Dawn of Hope, Meditation, Wanderers, and Conversation.

In 1960, he is commissioned to paint a portrait of the Mayor of Stoke Newington, Alderman Simon Cohen, which would hang in Stoke Newington Town Hall. Later that year it was shown as part of the ninth St Pancras Art Exhibition at Kings Cross. In 1963, he is commissioned to paint a portrait of Alfred Cooper, a district commissioner of the Scouts and a leader of the Jewish Scouting movement. Over the next seven years, he continues to develop his creative talents by attending part-time courses at the John Cass School of Art and the Camberwell School of Art.

His painting An Artist in Her Studio is selected for the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in 1965. In December 1968, he exhibits at the Guildhall in the City of London with the Cass Art Group. He also shows his work at the Northumberland Avenue Coffee House on Trafalgar Square.

In 1970, his last painting, An Artist at Work, is shown at the London Arts Association’s Greater London Exhibition.

He died on August 27 that year, at his home in Craven Walk, Stamford Hill, north London, aged 78.

Morris outlived all of his friends who were part of the Whitechapel Boys group and he continued to create new work long after their deaths. Isaac Rosenberg was killed in 1918 during the First World War in 1918, Mark Gertler committed suicide in 1939, Bernard Meninsky died in 1950, David Bomberg died in 1953, John Rodker died in 1955 and Jacob Kramer died in 1962.

Until now, however, the story of Morris Goldstein, the Lost Whitechapel Boy, has not been told.

1 Moorcroft Wilson, J: Isaac Rosenberg – The Making of a War Poet, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, UK, 2007

2Cohen, Joseph: Journey to the Trenches: The life of Isaac Rosenberg 1890-1918, Basic Books, New York, 1975

3 Located at Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives

4 Sarah MacDougall in London, Modernism and 1914, edited by Michael J Walsh, 2010

5 Archived at University of the Arts London, London College of Communication

6 Cohen, J: Journey to the Trenches: The Life of Isaac Rosenberg 1890-1918, Basic Books, New York, 1975,

7Hartley Library, University of Southampton

8 Tickner: Modern Life and Modern Subjects, Yale University Press, 2000 (p.149)

9 ibid, p. 280n28

10 Cohen, J: Journey to the Trenches: The Life of Isaac Rosenberg 1890-1918, Basic Books, New York, 1975, p.43

11 ibid, p.43

12 p.187 Moorcroft Wilson J: Isaac Rosenberg – The Making of a War Poet, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, UK, 2007

13 p.187, ibid

14 Cohen, J: Journey to the Trenches: The Life of Isaac Rosenberg 1890-1918. p.97

15Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall: The Whitechapel Boys, Jewish Quarterly.

16 Moorcroft Wilson, J: Isaac Rosenberg – The Making of a War Poet, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, UK, 2007

17 Cohen, J: Journey to the Trenches: The Life of Isaac Rosenberg 1890-1918, Basic Books, New York, 1975, p.204, Note 34

18 Tate Britain collection

19 Sarah MacDougall in London, Modernism and 1914, edited by Michael J Walsh, 2010

20 JEAS collection, Hartley Library, University of Southampton

21 Sarah MacDougall in London, Modernism and 1914, edited by Michael J Walsh, 2010

22 Author’s personal collection